How Canned Food Went From Military Rations to Fancy Appetizers

This simple technology changed the world.

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE NOVEMBER 11, 2023, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

Let me ask you a question. What pops into your mind, when you envision a can of food? For some of us, it’s a simple can of cream of mushroom soup. For others, the meal of the moment is an expensive tin of fish imported from Portugal.

Perhaps you get a sense of nostalgia seeing tinned pumpkin pureé, jellied cranberry sauce, and green beans neatly lined up on store shelves this time of year. Or your basement could be filled with cans of soup in case disaster strikes.

Grab a can opener, readers. Today, we’ll be cracking open the history of all things tinned.

War Fare

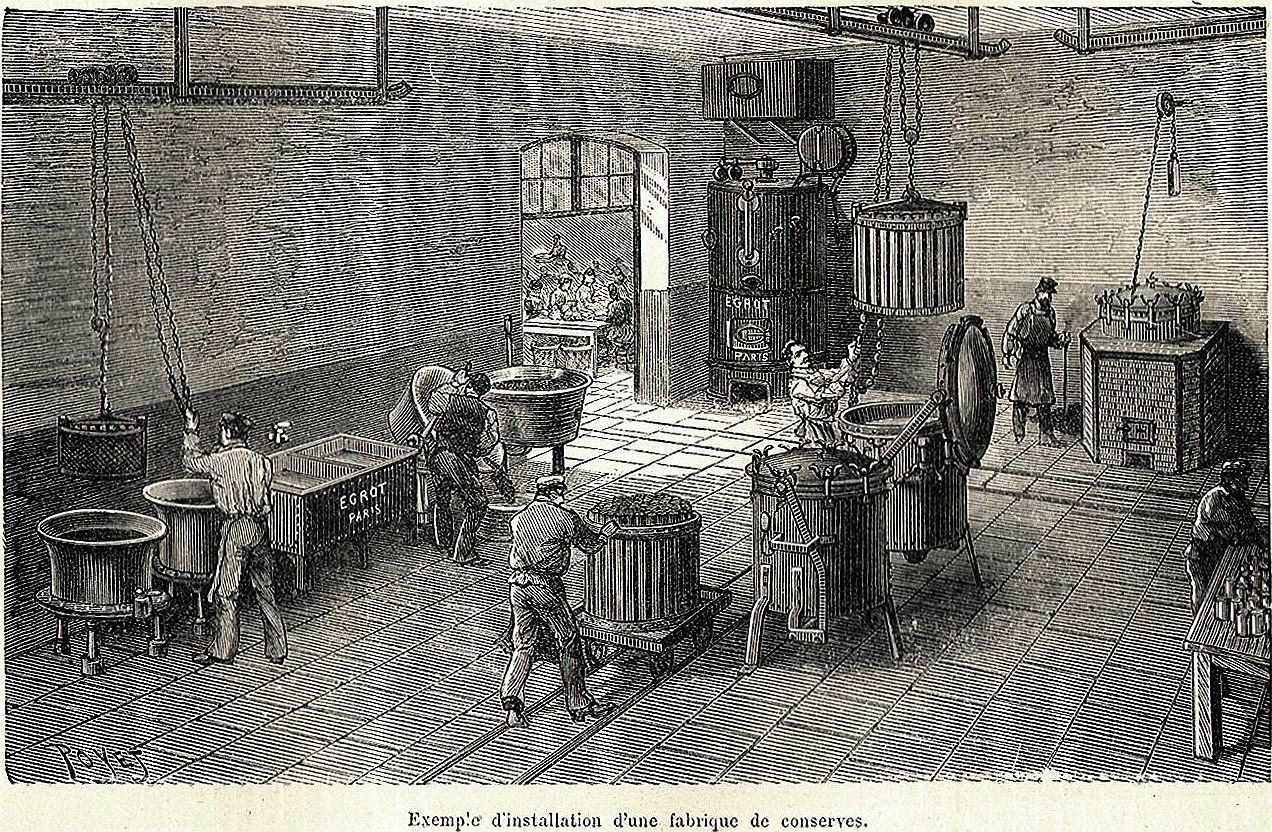

The story goes something like this: In the late 18th century, the French government issued a challenge to European inventors. Whoever could come up with an efficient way of preserving food for the French army would win a cash prize.

It took 15 years for anyone to succeed, but finally, a man named Nicolas Appert claimed 12,000 francs from Napoleon’s administration in 1809 by proving that heat-sealed containers could preserve meat, fruit, fish, and vegetables for an impressively long time.

The upcoming Napoleon biopic is not likely to include the origin story of canned food. Yet the need for more nutritious military rations resulted in that can of chickpeas sitting in your cabinet.

What’s In a Name?

There’s something I’ve been pondering for years. Why is it called “home canning” when people make pickles or preserves in their kitchens, with glass jars instead of cans?

“The canning word, and the reference to the can itself, is kind of secondary,” explains Anna Zeide. Zeide is an associate professor of history at Virginia Tech and the author of Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. In fact, she says, the process of hermetically sealing food and heating the containers to kill any bacteria was originally called “appertizing,”after Appert himself.

While Appert is known as the father of canned food, Zeide notes there’s a lot of research suggesting “that the method was not something he had started, that probably women in their homes had been doing something like it for a long time before him.” Not only that, but Appert didn’t use cans himself. Instead, says Zeide, he likely started out with ceramic containers sealed tightly with cork.

In 1817, William Underwood, a canner from England, immigrated to the United States. The William Underwood Company of Boston became prominent, supplying canned food to expeditions and Civil War combatants. Some sources consider Underwood to be the source of the word can, as well, claiming that the company’s bookkeepers began abbreviating the term tin canisters in 1839.

The Oxford English Dictionary points to an 1853 book called A Pictorial View of California: Including a Description of the Panama and Nicaragua Routes, with Information and Advice Interesting to All, Particularly Those who Intend to Visit the Golden Region as containing the first published use of the word can to describe a tin canister of meat.

Can-Do

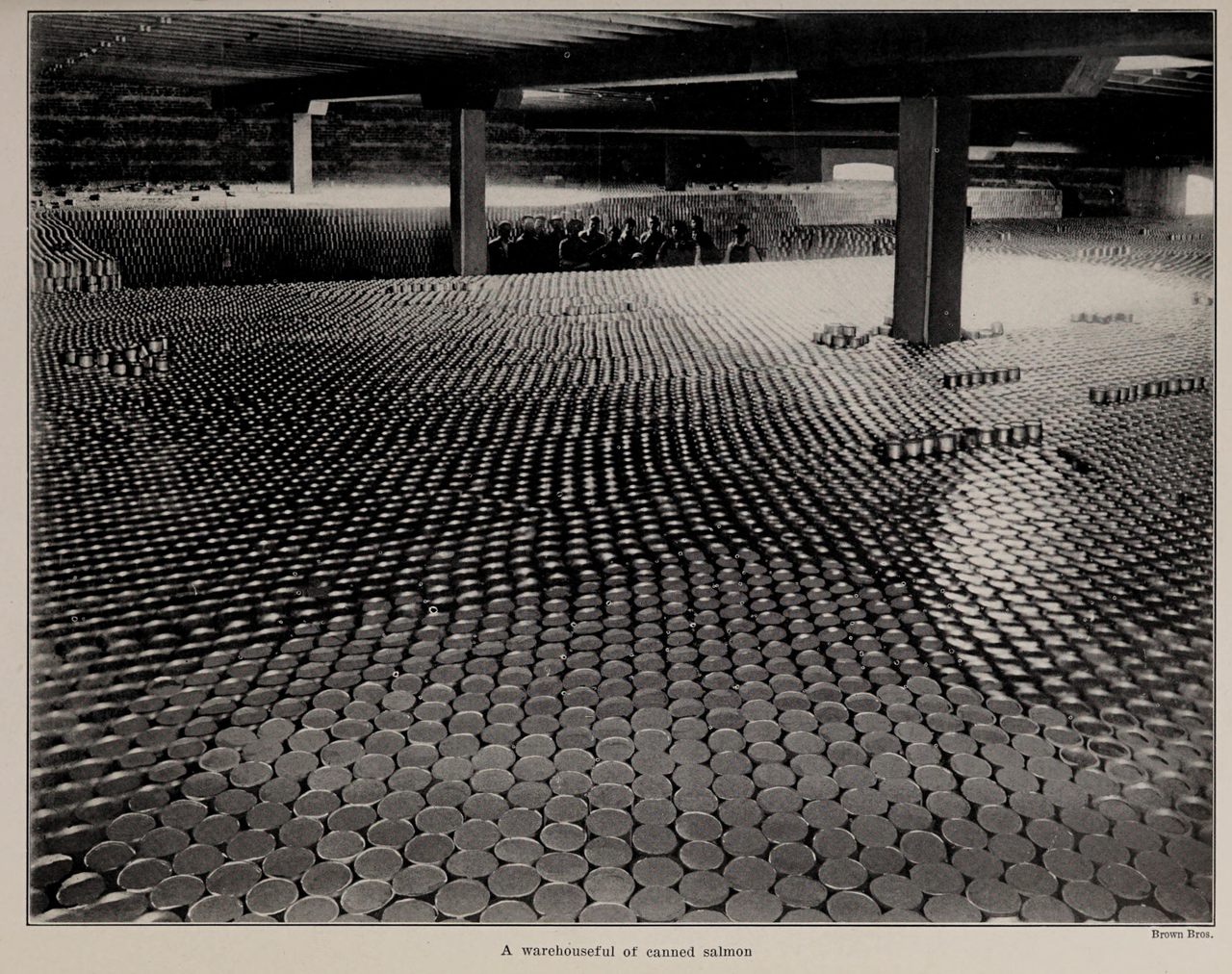

For soldiers, sailors, and settlers, canned food was a valuable resource, one that could handily prevent dangerous nutritional deficiencies. “In the mid-19th century, before the Civil War, canned foods were largely the province of people who were in extreme situations, whether it was Arctic explorers or people who were going to be sailing across the Atlantic for months,” says Zeide.

Canning also made foods available out-of-season and far from their origins, making them appealing to a different kind of clientele. “Wealthy colonists or immigrants were able to get tastes of their home country, or something like it, by shipping over these canned foods when they were really expensive,” she says.

But as canned foods became available to more people, skepticism about them grew. “Industrially canned foods, in these opaque containers that come from unknown places, the only thing you know about them is what’s on the label,” Zeide says.

“[There was] a stark difference from the way that consumers had really forever engaged with food, which was by picking it themselves, feeling its weight and its heft and its smell and its feel. To know if it was good, if it was ripe, if it was still fit to eat, if it hadn’t spoiled. All these things disappeared behind this opaque metal wall of the tin can.”

A Golden Age

But by the 1950s, the United States entered what Zeide calls “a golden age of processed food, a time when people really loved canned food.” Companies primed consumers by putting out cookbooks and programming aimed at extolling their benefits.

For homemakers used to making everything from scratch with what was locally available, it was a revelation. “It just felt like such an abundance, such access to so many convenient foods that reduced the labor of cooking, that reduced the time of cooking,” Zeide says.

While canned foods have lost quite a bit of their glamor since, Zeide points out that they’re still an immense part of our culinary lives. “The way that I talk about it is that canned foods became invisible rather than became out of favor, that people certainly continued to eat them.”

When it comes to public perceptions of canned foods, “it’s been kind of a rise and fall and rise and fall and rise and fall,” she says. Attempts have been made to recapture a bit of the midcentury magic, Zeide notes, pointing to a Campbell’s soup campaign from 2012 that targeted hipster tastes. “They put out Spotify playlists that set the mood for the food you were eating,” she says. “They put out these cat memes.” The soups from that product line, notably, came in plastic bags instead of cans.

A Long Shelf Life

I’d argue that canned food is currently gaining some glamour back. There’s the trend for conservas, especially in the form of canned seafood from Portugal and Spain that cool wine bars serve to customers still inside the tin. Even the humble canned bean is getting a glow-up, with the hoary bean brand S&W rolling out a line of heirloom varieties (pinquito, Jacob’s cattle) in contrast to their “classic beans.”

But in the end, no matter if I’m buying something exotic (steamed brown bread) or basic (garbanzo beans), I find canned food comforting. Sure, most canned foods have a use-by date, but tales abound of people eating canned products that are decades or even a century old.

“I do feel like canned food has this association with either canned-food drives and food pantries or apocalypse preppers,” says Zeide. “But the reason they’re such a staple of both of those spaces, really, is because 100 years from now, you could still eat a can of food. So it’s pretty cool that a fairly old technology can still really bring such value.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook