The Hidden Worlds of Monopoly

From Atlantic City to high fashion to Karl Marx, the most recognizable board game has had serious cultural impact.

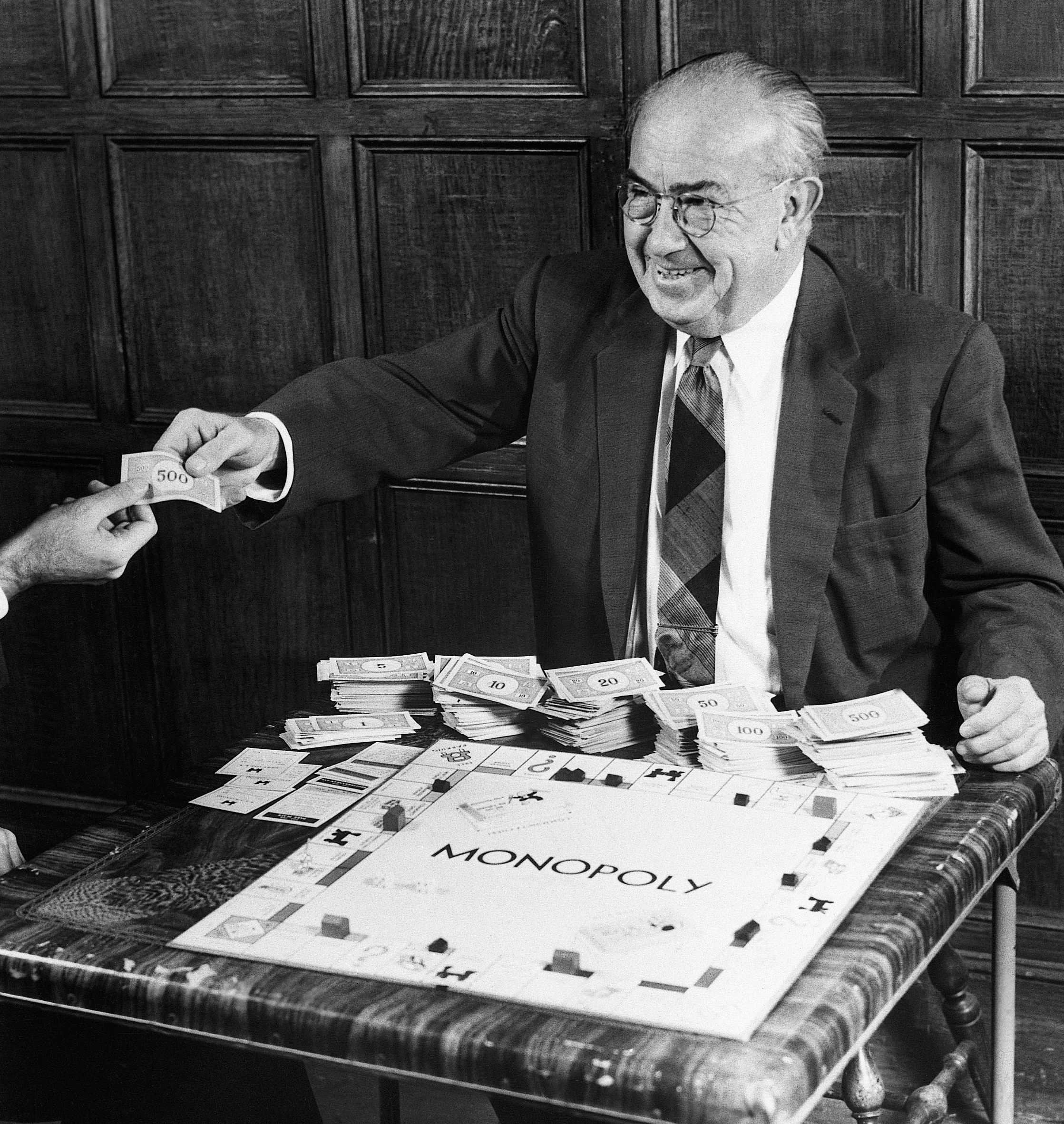

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Monopoly, patented on December 31, 1935 by Charles B. Darrow, is not a game: It’s a world. The basic template: a multiplayer economics game, in which players roll two six-sided dice, move around the periphery of a square board, buy properties, collect rent when opponents land on their spaces, and buy up or trade for connected properties to build houses and hotels on. You win when everyone else goes bust. Played the right way, it’s as much about psychological warfare as economics; sidebar wheeling and dealing is not only encouraged but necessary. Things have to keep moving, and generations of family and friends have convinced and cajoled, causing epic fights in households worldwide. (I wouldn’t know anything personally about that.)

Darrow’s Monopoly is set in Atlantic City, New Jersey, and the properties around the board mirror the one-time values of real estate on the actual streets of that city. The street names were genius from a game design perspective. Many of the town’s streets are named after states, so you get to travel the whole country block by block, which means that the town is both specifically a fun resort destination and Everywhere, America, at the same time. But there’s a troubling side there as well: the city’s deep racial and socioeconomic ghettoization surfaces in Monopoly’s setup. Baltic and Mediterranean, the cheapest properties on the board, correlate to historically ethnic neighborhoods (even in name), while the historically rich, white enclaves, such as Park Place and Boardwalk, constitute the game’s more expensive zones. In his 1972 essay “The Search for Marvin Gardens,” published in The New Yorker, writer John McPhee dramatizes gameplay, competing on the board and moving through the town simultaneously. For example, when he landed on Vermont Avenue, one of the game’s least expensive properties, he observed that “the dogs are moving (some limping) through ruins, rubble, fire damage, open gardens.” Marvin Gardens, on the other hand—on the more expensive half of the board, a coveted yellow, only bested by green and dark blue—is a historically white suburb, and the only property not in Atlantic City itself. The real-life three-street enclave is not actually “Marvin” but “Marven,” a portmanteau for the border of “Margate” and “Ventnor.” In 1995, Parker Brothers formally acknowledged the misspelling and apologized to the residents of the real Marven Gardens.

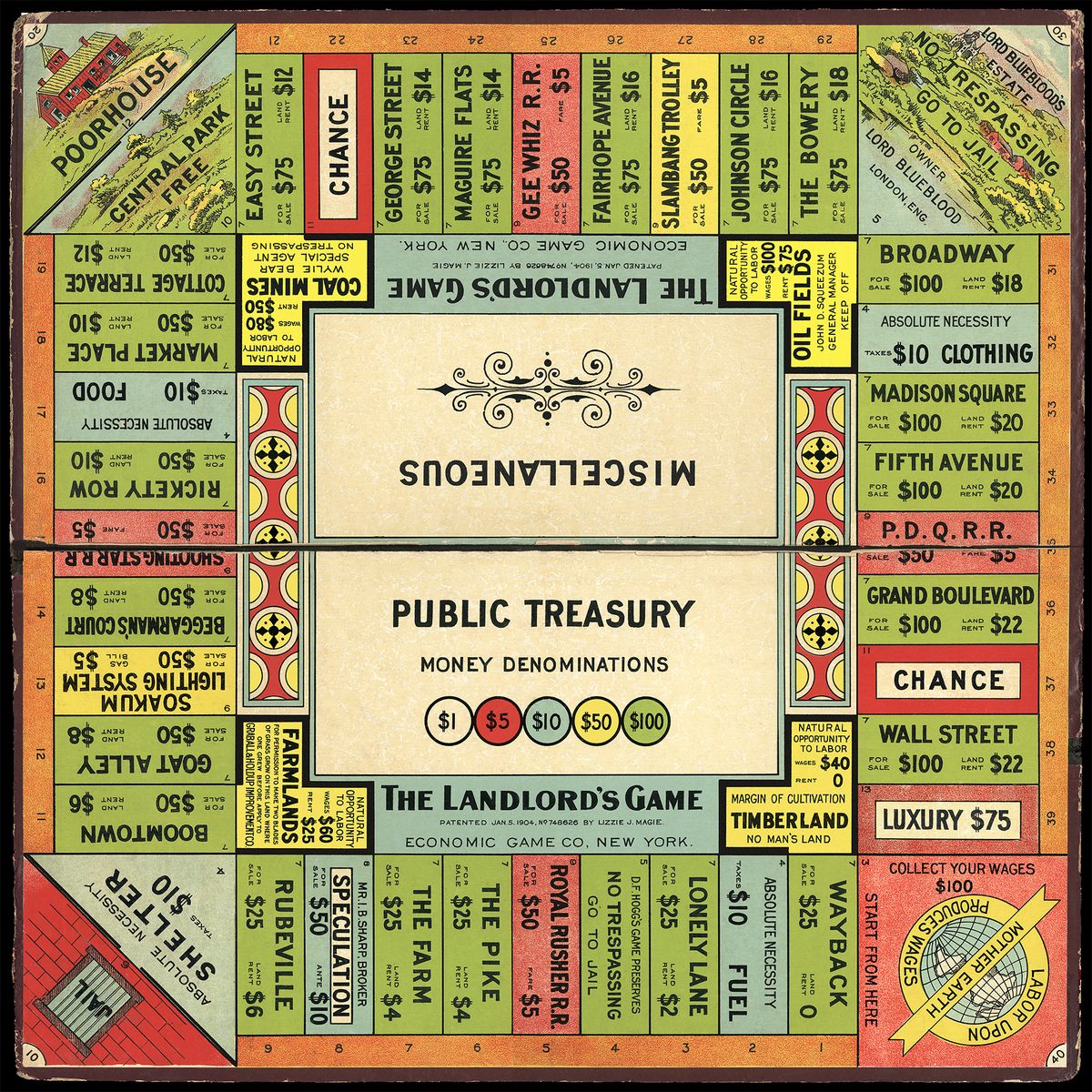

And Atlantic City Monopoly is itself a version of another game, a debt it doesn’t recognize for obvious reasons. In 1904, inventor Lizzie Magie patented The Landlord’s Game, at its heart an educational tool to teach players about taxes. The Landlord’s Game is the same concept and mechanism—players travel around a game board, buy properties, and pay each other rent. But there are crucial differences. For one thing, the game is criticizing, not celebrating, landlords: The purpose is to show players how rents put money into the coffers of fatcat landlords while impoverishing tenants. There are monopolist and anti-monopolist versions of the rule set. Darrow’s 1935 version, while in many ways a copy of Magie’s, misses the original point: The goal of his game is to revel in the fantasy of being a land-grabbing property owner who bleeds renters dry and uses under-the-table deals to create structural inequality. Barring incredible dice luck, you can only win at Monopoly by dominating trades.

It is also a truth universally acknowledged that Monopoly is a bad game, especially in the board game bonanza we currently live in. The original gets a 4.4 out of 10 rating from more than 35,000 voters on boardgamegeek.com, a popular forum and games database. Though you can, of course, play the original Monopoly, why would you? There are countless adaptations, though they don’t actually make the game any better, since the vast majority are essentially skins. The standard British version, released contemporaneously with the American version in 1935, features locations around London. There’s Animal Crossing: New Horizons Edition, FIFA World Cup 2006 Germany Edition, Game of Thrones Edition. Near the real-life Marven Gardens recently, I saw a pillow embroidered with “Ventnoropoly”—the Inception of Monopolies, a meta-wormhole in which a single property on the original board is expanded to contain an entire Monopoly of its own.

The nadir of the Monopoly Cinematic Universe might be Ms. Monopoly, an incredibly cringe version that Hasbro released in 2019. Ms. Monopoly featured inventions by women in lieu of properties—Oriental Avenue was reimagined “Modern Shapewear,” Boardwalk as “Chocolate Chip Cookies”—and was intended to course-correct societal inequities by giving female-identifying players monetary advantages. It flopped hard: The media had a field day lambasting the game’s “patronizing pointlessness,” as Madeline Kearns wrote in the National Review. Putting lipstick on Uncle Pennybags (in the form of a character identified as his niece) didn’t exactly upend the patriarchy. And, as Mary Pilon, author of The Monopolists, a history of the game, observed inThe New Yorker, Ms. Monopoly pointedly failed to recognize, either in the press release or the gameboard itself, another invention from a female: The Landlord’s Game.

Where Monopoly actually does get good is in its real-life applications. It might not be much fun to play, but it’s fantastic as a vibe. Monopoly is fashionable. On the Boardwalk end of the spectrum, luxury designer Olympia Le Tan produced a limited-edition set of Monopoly that featured the game’s deeds embossed and embroidered on multi-thousand-dollar clutches. In season two of … And Just Like That, the reboot of Sex and the City, Sarah Jessica Parker’s character Carrie Bradshaw sports a vintage sweatshirt with “New York Monopoly,” a graphic loosely based on the look of the board (“Shopping Spree at Bloomie’s” instead of Free Parking, and “Attend the Met Gala” instead of passing GO), which should not be confused with the actual New York City Edition, a playable version of the game. (Though it might be impossible to nab a vintage sweatshirt a la Bradshaw, you can cop legions of copycat tops at Baltic Avenue prices from across the internet).

Monopoly has a long enough history that it has done more than champion capitalism and wreck families. During World War II, British intelligence created doppelganger game boxes that they sent to POWs, containing not the original board, but maps and tools to help them escape. And Monopoly has quietly returned to its educational roots. The game is frequently used in economics and behavioral psychology settings. For example, University of Tampa sociologist Ryan T. Cragun created different rulebooks for Monopoly to simulate starting with various socioeconomic advantages and disadvantages (“Capitalism: Race, Ethnicity, and Sex/Gender Discrimination Version,” “Communism: Marx’s Version”). Paul Piff at the University of California, Berkeley, concocted a study using Monopoly to demonstrate how privilege impacts personality. When Piff randomly gave some gamers an advantage at the beginning, these players almost immediately turned into alpha dogs. They “began to move their pieces around the board more loudly, displayed ‘signs of dominance and nonverbal displays of power and celebration,’ ate more pretzels, and became ‘ruder, less and less sensitive to the plight of the poor players, and more likely to showcase how well they were doing.’” The really wild finding was the lucky players’ self-congratulatory mindset: “After the game, the rich players attributed their success to their skills and strategy, not the systematic advantages they had over the other player, even though they knew the advantages were real and were randomly assigned.”

Playing Monopoly may be objectively flawed—stolen property, wealth inequality, family feuds, socioeconomic disparity—but its place in modern culture is more robust than ever. And ironically, Monopoly’s applications in the real world often critique the very things the game itself champions. We may never get to play the anti-monopolist version of Magie’s The Landlord’s Game anymore, but maybe we could try living it.

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them, a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice; What Was It For, winner of the Rescue Press Black Box Poetry Prize; and Our Dark Academia.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook