At Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Is Still Growing

Restoring the grounds and its rare, heirloom crops recreated what was effectively the country’s first seed bank.

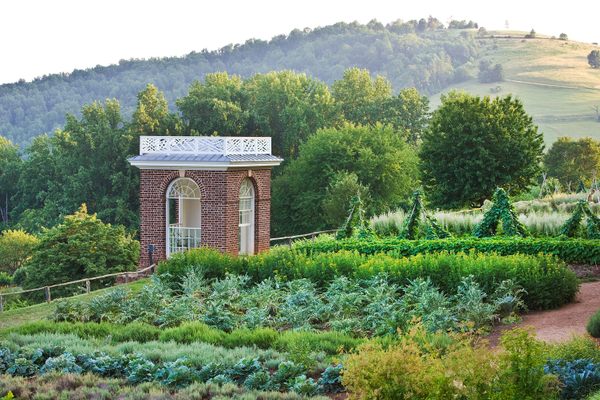

A short downhill walk from Thomas Jefferson’s historic Monticello mansion, there is a two-acre terrace garden carved into the hillside and supported by a massive stone retainer wall. Blessed with panoramic views of the Virginia countryside, it holds more than 330 varieties of more than 70 species of heirloom vegetables, and dozens of herbs. Just below, an eight-acre “fruitery”—a 400-tree orchard and vineyard with berry patches—contains at least 170 historically significant varieties of more than 30 species of fruit.

The result of a massive construction and restoration effort, these grounds replicate the collection of botanical treasures Jefferson assembled from 1770 to 1826—rarities such as 14-inch-long Cow’s Horn okra from Africa and bulbous Purple Calabash tomatoes from Mexico grow alongside Indigenous American, melon-like Green-Striped Cushaw squash and long and carrot-esque China Rose winter radish.

“These gardens were the embodiment of Jefferson’s love affair with culinary plants,” says retired director of gardens and grounds, Peter Hatch, 70, who spent 34 years reconstructing Monticello’s historical horticultural operations.

The third U.S. president’s interest in fruits, vegetables, and spices was obsessive and indulged on a grand scale. From the perspective of ingredients, Hatch calls Jefferson early-America’s foremost culinary connoisseur.

“His devotion to obtaining rare varieties and experimenting with cultivation techniques bordered on religious,” says Hatch. “He dedicated more writing to the subject, about 700 pages, than any other.”

As an evangelical byproduct, Jefferson founded what was arguably the nation’s first seed bank.

“He would hear about a ‘new’ vegetable and have to have it,” says Hatch. If growing experiments proved fruitful, seeds, taste descriptions, and instructions were mailed to “everyone he knew”—including George Washington, James Monroe, and James Madison. The efforts helped introduce then-obscure ingredients such as tomatoes, eggplant, and okra into mainstream usage.

When Hatch arrived at Monticello, Jefferson’s garden had almost entirely disappeared. He made it his mission to restore both its grounds—with a museum’s eye for historic accuracy—and its mission as a seed bank and resource for American farmers. The garden and fruitery now serve as the backbone for the Thomas Jefferson Center for Historic Plants, which sells historical seeds and grafting stock, and offers educational programming centered around heirloom gardening, viticulture, and pomology. Hatch’s successor, Keith Nevison, 36, is transforming the Center’s 650-acre Tufton Farm, which he manages, into a learning and research center for sustainable small-scale farming.

Nevison says the project will allow the Center to “bridge the past, present, and future of a very Jeffersonian form of agriculture.”

The COVID-19 pandemic is validating the statement. The Center usually sells about 92,000 seed packets a year. Orders for 2020 surpassed that number by April 1, says Nevison, “and continue to flood in.”

Getting to this point, says Nevison, has taken tremendous effort and ingenuity. It began with Hatch’s arrival at Monticello in 1977—when neither the terrace garden nor fruitery existed, much less the Thomas Jefferson Center for Historic Plants or Tufton Farm’s educational complex.

Jefferson’s debts forced his family to sell the property when he died in 1826. When the Thomas Jefferson Foundation purchased 650 of its original 5,000 acres in 1923, both house and gardens were, according to the Virginia Historical Society, in practical ruin. Restoration efforts focused on buildings and surrounding landscaping. The Garden Club of Virginia reconstructed flowerbeds, but the contents weren’t historical.

Meanwhile, orchards had been sawed down, berry patches overrun. The terrace garden’s massive stone retainer wall had been looted by the Civilian Conservation Corps; erosion had returned the area to grassy hillside.

Hatch was hired to change all that. Says Gabriele Rausse, the father of Virginia wine and Monticello’s current director of gardens and grounds, “He was tasked with affecting what quickly became the most meticulous and painstakingly accurate horticultural restoration in U.S. history.”

Hatch had made a name for himself using archaeological evidence and written records to replicate 18th-century gardens at Old Salem in North Carolina. He was part of a new vanguard of preservationists dedicated to bringing historical foodways to life.

Efforts at Monticello began with infrastructure. Hatch pored over Jefferson’s historic journals, garden diaries, correspondence, and landscape drawings. The research guided archaeological digs that pinpointed locations for fence posts, retainer walls, vegetable beds, and fruit trees.

“Jefferson made new [garden-related] drawings and plans constantly,” says Hatch. Many were abandoned, others partially implemented and soon replaced. “He was always adding this, taking away that … It was impossible to tell, exactly, what was where and when.” The digs helped establish the true state of the grounds, but Hatch also added unrealized ambitions of Jefferson’s—like boutique vineyards filled with European wine grapes.

But as Hatch excavated and researched, he wasn’t just looking for records of plants and Jefferson the gardener—he was looking for slave labor and Jefferson the plantation owner, too.

“To me, this was a fundamental aspect of the project,” says Hatch. Whereas Monticello had once essentially avoided the subject, Hatch sought to acknowledge and explore it directly.

“That’s the only way to paint a complete portrait of Jefferson the horticulturist,” he says. “You have to present the realities of slave ownership. And we wanted to build that information into our educational model from the get-go.”

Research revealed that teams of enslaved people had spent years leveling the garden site, building ornate stone walls, and hauling fertile topsoil up the mountain by way of mule and cart. They dug deep trenches to keep cattle out and built a .75-mile-long, 10-foot-high board fence that Jefferson bragged wouldn’t “let even a young hare in.” They installed cisterns to gather water from rooftops and irrigation systems to distribute it. The list goes on.

“Astonishingly, Jefferson insisted on doing much of the actual planting, tending, and harvesting himself,” says Hatch. But he relied on a few trusted, older enslaved men to help, particularly in the fruitery. Some underwent training with top European pomologists and gardeners. All were encouraged to grow their own vegetable gardens and sell produce to the house.

Hatch has written extensively on the subject—both on Monticello’s website and in his 2012 book, A Rich Spot of Earth: Thomas Jefferson’s Revolutionary Garden at Monticello. Today, plaques around the garden and fruitery, as well as tours, commemorate the contributions of those skilled workers, and acknowledge their forced servitude.

With the terrace and fruitery mapped and restored, Hatch began re-collecting plants. Hurdles proved considerable.

“Most of what we know about Jefferson’s collection is found in garden notes and letters,” says Hatch. For instance, Jefferson frequently wrote to leading U.S. horticulturalists requesting seeds for obscure varieties like Leadman’s Dwarf pea, Egyptian onion, and Early York cabbage. Elsewhere, he noted receiving Arikara snap beans, wild salsify, and Pawnee corn gleaned from the Lewis and Clark expedition.

“But Jefferson didn’t always use proper names to refer to vegetables,” says Rausse. A favorite pea might bring a detailed description, but take the name of the farmer that grew it. Appellations for many varieties changed with time, or varied by region. Others simply vanished.

“Peter became like a botanical detective,” says Rausse, who partnered with Hatch in the early 1980s to install vineyards for wine production based on Jefferson’s plans. Hatch spent years collecting and combing through nursery and seed catalogs from the 1700s and 1800s for names and clues. He developed relationships with experts at what is now the National Laboratory for Genetic Resource Preservation in Colorado and the Seed Savers Exchange in Iowa. He consulted with leading plant historians and visited historical gardens and orchards throughout the United States and Europe to compare Jefferson’s drawings to living plants.

Progress came slowly. Some items, like the French Purple artichoke, were easy to obtain. Others proved difficult.

“Jefferson referred to ‘the black plum peach of Georgia,’ but that name had long fallen out of usage,” says Hatch. After tracing early U.S. nursery references through two centuries of catalogs and various name changes, he discovered the peach was now called Indian Red or Blood Cling. He tracked down growers and obtained grafting stock for both. Then he waited for fruits and compared the results to Jefferson’s notes. The closest match was kept.

Hatch’s project was formalized as the Thomas Jefferson Center for Historic Plants in 1986. He began selling seeds and grafting stock, and developing educational offerings, soon thereafter. The Center’s scholarly “Twinleaf Journal” launched in 1990. The additions positioned the Center as an intersection for scientific discussion among plant historians, gardeners, orchardists, and botanists.

Nevison, the Tufton Farm manager, learned of Hatch’s work while studying at the University of Delaware’s prestigious Longwood Graduate Program in Public Horticulture.

“If you’re in this field, you know Peter Hatch,” says Nevison. With the Center, Hatch “created a model for everything a historical garden and nursery could and should be.”

Nevison aims to affect a similar revolution at Tufton. To do it, he’s asking the question: If Jefferson was alive today, what and how would he be farming?

Considering Jefferson’s passions for gastronomical diversity, horticultural experimentation, and ecological conservation, “We think he’d be going bananas over the modern farm-to-table movement,” says Nevison, who came to Tufton in 2018. “He’d almost surely be pushing the envelope of sustainability.”

Rausse and Hatch agree. With thousands of heirloom tomatoes now in circulation alone, they imagine Jefferson growing thousands of obscure varieties of fruits and vegetables. At minimum, seeking to optimize taste would drive experimentation with organic methods.

Nevison envisions Tufton as a regional, modern, educational farming center aligned with those projections. Plans include experimental cider orchards, hopyards and vineyards, groves of nut trees (including newly reintroduced American chestnuts), grain production, free-range, heritage-breed livestock, a food forest, and more.

“We want Tufton to be a go-to resource for beginner and veteran small-scale farmers alike,” says Nevison.

Early phases of development include partnerships with agricultural producers, specialty grocers, and colleges and research institutions. Small-scale farming gurus such as Joel Salatin of Polyface are consulting about best practices for free-range livestock and related research gaps. The Virginia State Beekeepers Association is helping with pollinator gardens and experimental beehives. The Livestock Conservancy is discussing programs aimed at raising endangered breeds of sheep, cows, pigs, and poultry. Virginia Tech and Virginia State University are involved as well.

Support for farmers will take a variety of forms, says Nevison.

He sees Tufton researching and disseminating scientifically validated best practices, developing hands-on learning opportunities, running a community kitchen for processing value-added products, helping with environmental certifications, and offering grant assistance for startups and expansions. Nevison also hopes to expand the Center’s nursery, orchards, and seed bank to include more varieties and conduct economic studies based on demand and market pricing. He wants to host farm dinners with regional chefs, conduct onsite vegetable and fruit tastings, and help connect farmers with restaurants, brewers, vintners, and grocers.

All of that, says Rausse, is a very Jeffersonian endeavor.

“This was a man that lived by the mantra, ‘The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add a useful plant to its culture,’” he says. “If Jefferson knew we were doing this, I think he would approve, but probably also be quite jealous—he’d want to be out here in the thick of things, getting his hands dirty!”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook