Chowder Once Had No Milk, No Potatoes—and No Clams

The earliest-known version of the dish was a winey, briny, bready casserole.

Iconic recipes have to come from somewhere. Welcome to First Draft Foods, where this week we delve into the legends and controversies behind the world’s favorite dishes. Previously, we learned about the origins of red velvet cake.

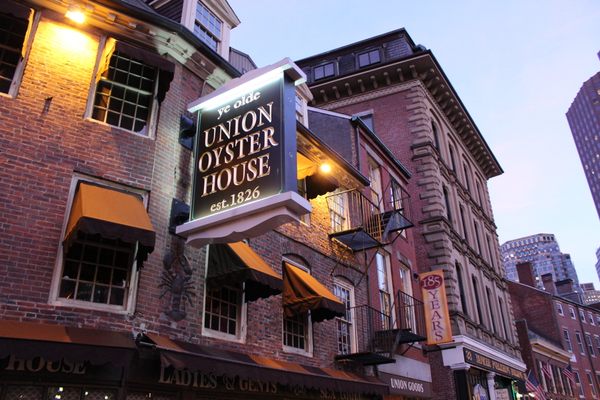

Clam chowder stands alone. Soupier than an average stew, chunkier than an average soup, it bubbles away at dockside restaurants and behind buffet counters. In the United States, it’s one of the few foods that’s both a cafeteria staple and a special-occasion meal.

Chowders don’t necessarily require clams—other types of seafood or even vegetables can be the soup’s centerpiece, and regional variants abound. But the bone-white, clam-filled version is by far the most popular. The earliest-known recipe for chowder, though, produced a dish that looked and tasted nothing like its modern counterpart. No milk. No potatoes. Even clams didn’t make it into the mix. Instead, the earliest known chowder was a winey, briny, bready casserole.

In a 1751 edition of the Boston Evening Post, an anonymous writer published a poem:

First lay some Onions to keep the Pork from burning,

Because in Chouder there can be no turning;

Then lay some Pork in Slices very thin,

Thus you in Chouder always must begin.

Next lay some Fish cut crossways very nice

Then season well with Pepper, Salt, and Spice;

Parsley, Sweet-Marjoram, Savory and Thyme;

Then Biscuit next which must be soak’d some Time.

Thus your Foundation laid, you will be able

To raise a Chouder, high as Tower of Babel;

For by repeating o’re the Same again,

You may make Chouder for a thousand Men.

Last Bottle of Claret, with Water eno’ to smother ‘em,

You’ll have a Mess which some call Omnium gather ‘em.

This is the first-known recipe for chowder, and nearly everything about it seems at odds with our modern milky stew. This recipe does include onions and preserved pork, much as modern chowder has onions and bacon, but instead of potatoes, the recipe calls for biscuits (likely ship’s biscuits, or hardtack) as well as a lush medley of herbs. Most noticeably, the recipe instructs the cook to layer the raw fish and biscuits in layers within a pot, soak the entire stack with red wine and water before cooking, and, noticeably, warns against any “turning,” or stirring.

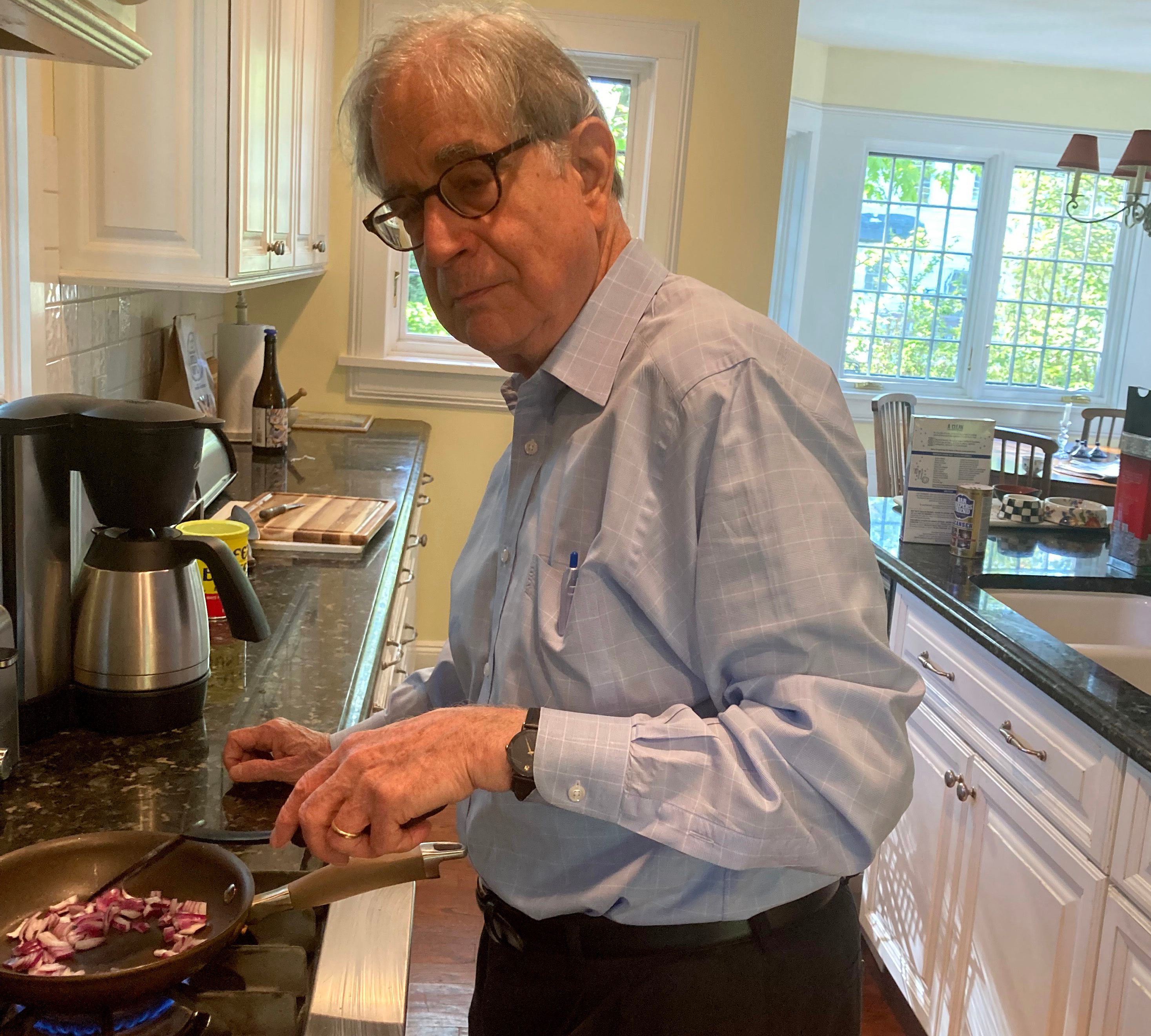

Then there’s the fact that the recipe was written as a poem. According to Paul Freedman, professor of history at Yale and the author of American Cuisine: And How It Got That Way, it was likely meant to be a parody of the era’s poetry-mania. “What is popular is dashing off poems about all sorts of things,” he explains. “In the 18th and 19th centuries, gentlemen liked to write poems for all sorts of non-solemn occasions.”

To readers, this chowder ditty would have been a hilarious send-up of more sincere poetic efforts published in colonial American newspapers. But, Freedman says, its existence implies that many Bostonians would have already known what chowder was in 1751. “You wouldn’t introduce a recipe for a completely new thing that people had not really heard of in the form of a poem,” he says. “Or if you did, you would make sure that you indicated that this is something new, that you, dear reader, have not heard of.”

Scholars have long speculated that chowder didn’t originate in New England at all. But both the name and ingredients give clues about how it may have landed in the region and, eventually, in Boston. The etymology of the word is murky, but chowder could be derived from chaudière, a French word for “boiler.” In the Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, food writer John F. Mariani notes how most scholars believe that Breton sailors who fished on the Canadian coast came up with chowder as a way to eat some of their catch. But, Mariani points out, other theories involve an origin in Cornwall, where in the local dialect jowder meant “fishmonger.”

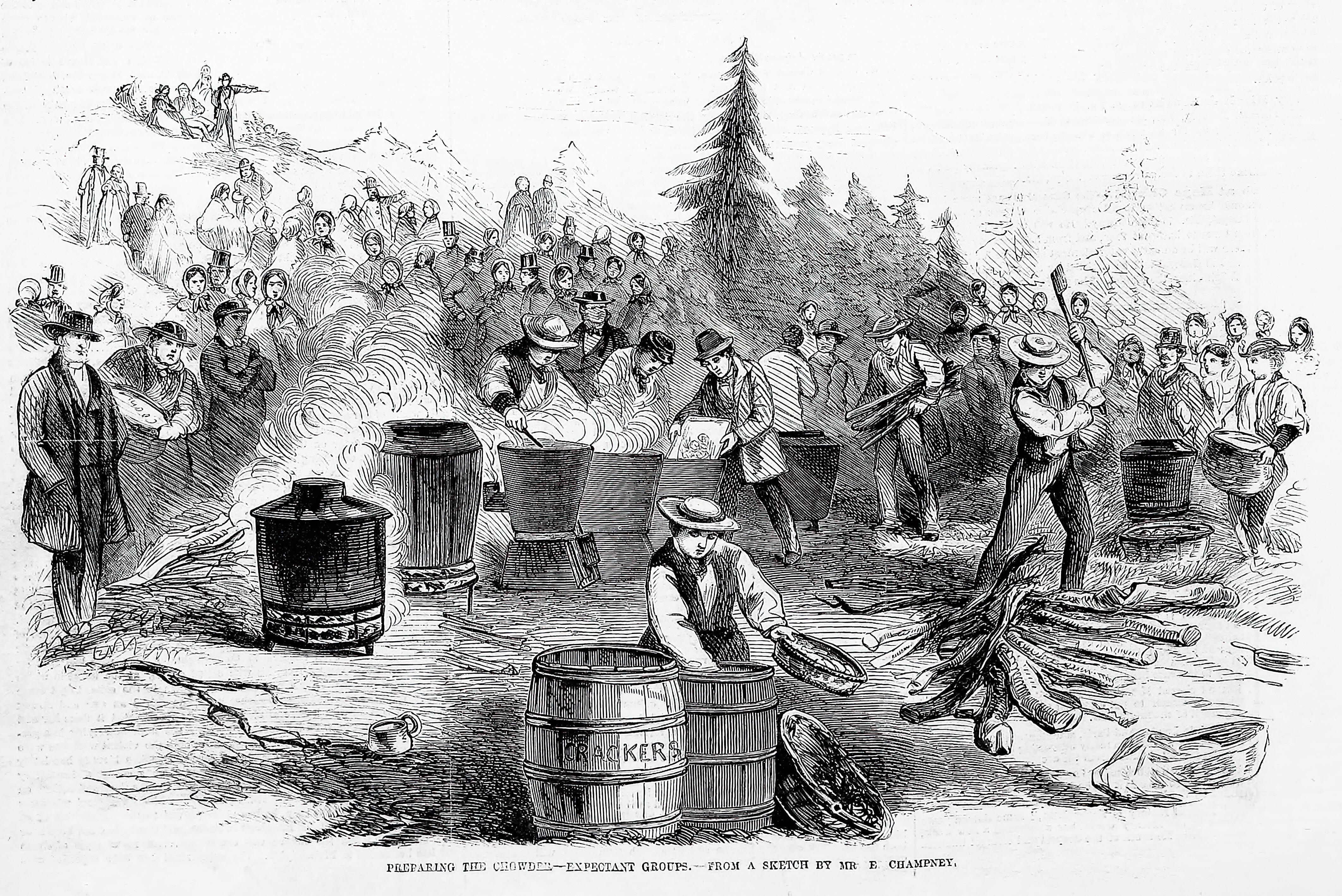

Undeniably, though, chowder was the food of seafarers, lending some credence to the Breton sailor theory. It would have been possible, even easy, to make chowder onboard a ship. Most of the ingredients, such as hardtack, salt pork, and wine, were common supplies.

Wherever its origin, chowder was common enough to become a staple across the Eastern Seaboard by the early 1800s. By the time it began appearing in cookbooks, the recipe had started to standardize into what would be recognized as “chowder” today. In Lydia Maria Child’s The Frugal Housewife, first published in 1829, the recipe still calls for fish, but there’s none of the wine that had soaked earlier versions.

Child’s recipe does share many similarities with the 1751 poem version of chowder. For example, she instructs the cook to start by frying salt pork in a large pot, but to remove it and leave behind the fat before starting to layer in the other ingredients: fish and crackers, as was traditional, but also potatoes. Instead of alcohol, a mixture of flour and water provided the liquid. No herbs are present. Instead, Child called for simply salt and pepper, along with a number of optional seasonings, including a sliced lemon, a cup of ketchup, a cup of beer, or even a handful of clams.

Clams only slowly became the preferred seafood for chowder. In the first half of the 19th century, fish chowder and clam chowder existed simultaneously, illustrated by, of all things, the 1851 book Moby-Dick.

In Moby-Dick, Herman Melville devotes an entire chapter to chowder, but not before giving his characters a choice between “Clam or Cod?,” as an impatient innkeeper demands to know. Ishmael, Melville’s protagonist, opts for the former. “It was made of small juicy clams, scarcely bigger than hazel nuts, mixed with pounded ship biscuits, and salted pork cut up into little flakes! the whole enriched with butter, and plentifully seasoned with pepper and salt,” declaims Ishmael. The cod chowder, which he tries next, is just as good, but possesses “a different flavor.”

But this delicious-sounding mess was still not really a milky soup like modern chowder. In fact, cookbooks well into the 19th century still noted that milk could be left out entirely, relying instead on potatoes, crackers, and water for creaminess. In Miss Parloa’s New Cookbook, first published in 1880, a fish chowder recipe stated that while milk was optional, the chowder should be allowed to boil before serving: a sign that the dish was no longer a mushy casserole, but a soup. And not just any soup, but a treasured part of American culinary culture.

Specifically, it had become an important part of New England cuisine. “In the 1880s, there’s a colonial revival visible both in furniture styles and in housing design. New England becomes a kind of cozy Sturbridge-Village nostalgia thing for the first time,” Freedman says. (Old Sturbridge Village is a living-history museum in Massachusetts.) The values, handicrafts, architecture, and foods of colonial-era New England gained a golden glow in this era, due to nationwide celebrations of the 100-year anniversary of the founding of the United States. The elevation of such a humble period isn’t without irony. “Beforehand, it was just the way we lived when we were poor,” says Freedman.

Some of that glow rubbed off on chowder. “My guess would be that the first people who could afford to eat something fancier but chose clam chowder would [exist] around that time,” Freedman says.

Today, you can eat creamy, clam-filled chowder across the United States, well beyond New England. Some derivations from the standard have popped up, especially in regions where clams are not as present. Inland, corn, smoked salmon, and even squirrel meat have made their way into the chowder pot over the centuries.

But this story would not be complete without mentioning New England clam chowder’s nemesis. Manhattan clam chowder, the tomato-laced version of the soup, has historically been treated with almost overwrought disgust for its derivation from the current milky norm. In 1939, a state legislator in Maine even wrote up a bill to have it outlawed.

To Freedman, the hysteria over red tomato chowder is merely a performative debate, considering that the white kind has so emphatically won the cultural battle. Instead, “it’d be hard to find a Manhattan clam chowder advocate,” he says. “No person of taste and culture actually is going to put tomatoes in their clam chowder.”

Fish Chowder

Adapted from the 1751 poem "Directions for Making a Chouder"

- Prep time: 15 minutes

- Cook time: 20 minutes

- Total time: 35 minutes

Ingredients

- ½ white onion, sliced

- 9 ounces hardtack (see note)

- 5 slices bacon, halved

- One pound firm white fish, in 2-inch slices

- ½ teaspoon salt

- ½ teaspoon pepper

- 1 teaspoon dried marjoram

- 1 teaspoon dried parsley

- 1 teaspoon dried thyme

- 2 cups red wine

- Water

Instructions

-

Spread the sliced onion in the bottom of a heavy pot. Sprinkle the sliced fish with salt, pepper, and the dried herbs.

-

Start layering! Lay four slices of the bacon over the onions, then a layer of fish, and finally, some pieces of hardtack. Follow with another layer of bacon, more fish, and hardtack, until you run out of ingredients.

-

Pour the wine over the layers along with enough water to just cover the ingredients, and set the pot on a stove. Cook on medium heat for about 20 minutes. The hardtack will absorb most of the liquid, so keep an eye out for any scorching.

- Take the pot off the stove, and check to make sure the fish is done. Serve immediately in bowls.

Notes and Tips

Recipes for old-fashioned hardtack abound online, as do ways to buy it. The amount of liquid your hardtack will absorb may vary, but it should be soft before eating.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook