Make Ancient Roman Brain and Rose Soufflé

Somebody in the fifth century combined these ingredients into one recipe, and probably no one has since.

There are some food pairings that just seem meant to be. Peanut butter and jelly. Rice and beans. Brains and eggs.

Of course, nowadays, you won’t see brains and eggs on a menu too often, but before concern over the “Mad Cow” outbreak of the early 2000s and other factors shifted our preferences, brain and eggs was a popular breakfast pairing in the American South, up until as recently as the mid-1900s. It was also a common combination in fifth-century Rome, if the most-complete surviving Roman cookbook is any indication.

De re coquinaria, meaning “On the Subject of Cooking,” is often known as Apicius after its alleged author. And Apicius, or whoever it was that wrote the book, offered numerous recipes that pair brains with eggs. For some of these preparations, Roman chefs poured beaten eggs into a dish layered with whole brains, meats, and vegetables before baking. This belonged to a broad category of dishes called patinae, after the round, flat dish they were cooked in, like the modern term casserole. However, while a patina made with whole brains probably resembled a modern frittata or quiche, other examples of brain-and-egg patinae in Apicius might have been lighter and airier, like a soufflé, based on differences in the cooking instructions.

For these recipes, Apicius tells us to mash the brains into a paste after blanching them and removing their outer membrane by pressing them through a strainer. Then, the gray matter gets blended with beaten eggs and other ingredients before being cooked gently in a double-boiler, or in termospondio (“in the ashes”). This entailed covering the patina with a lid and nestling it among the coals at the outer edge of the fire, where the temperature was lower. One such dish, made with reduced wine, brain paste, milk, spices, and eggs, was commonplace enough that Apicius called it the patina quotidiana, “everyday patina.”

Another, more unusual example was the patina de rosis, made with brain, eggs, sweet wine, pepper, and rose essence. Although the concept of a brain soufflé may seem odd to us today, recipes for the dish can be found in 19th- and early-20th-century European cookbooks. And in Trentino in the far north of Italy, a possible modern descendant of the Roman brain soufflé lives on as budino di cervello e funghi, “brain and mushroom pudding.”

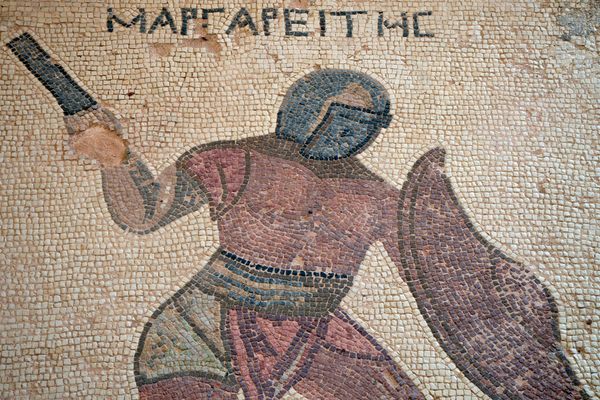

Brain is a rich, fatty organ meat with a mousse-like texture and a flavor similar to liver. Soufflés take advantage of the delicate creaminess of cooked brain for a uniform texture, rather than contrasting it against denser ingredients. At Roman banquets, soft textures were especially appreciated because diners typically did not eat with knives or forks, or have their own plates at the table. Instead, they scooped morsels from communal dishes using their own personal spoons.

Brains show up in many other Apicius recipes as well. They were mixed into porridge or peas and used in the filling for sausages, gourds, roasts, and whole squids. These recipes typically called for calf or pig brains, sometimes interchangeably, and while Apicius doesn’t contain any recipes for bird brains, there are references in Roman literature to these being eaten as well. The third-century Emperor Elagabalus reputedly served platters heaped with the heads of thrushes, pheasants, peacocks, parrots, and flamingos at his infamously opulent banquets (the flamingo’s large, muscular tongue was also a delicacy). “At one dinner where there were many tables,” claimed a fourth-century biography of Elagabalus, “he brought in the heads of six hundred ostriches in order that the brains might be eaten.” These stories of decadence, copied down long after an unpopular emperor’s assassination, were likely exaggerated to enhance his immoral reputation. Even the brain-loving Romans would have thought 600 at one dinner was a bit much.

Brain, with its rich, fatty texture and relative scarcity, would have been regarded as an exclusive luxury food to begin with, and despite Apicius’s “everyday” moniker, the recipes in the book generally represent the indulgent delicacies of an elite minority, not the standard Roman diet. Apicius’s rosy brain pudding may have been no less alien to the average Roman than it is to the average person today. However, the unique yet simple combination of ingredients does present the modern home cook with an intriguing challenge…if you’re up for it.

If you’ve made it this far, you’re probably wondering, “Where do I find animal brains for sale these days?” In the United States and some other countries, adult cow brains are now illegal to sell for food because they may carry BSE or “Mad Cow Disease.” There is also concern about a similar disease carried by wild North American deer and elk. However, many other animal brains, including those of young cows, do not pose the same risk. Pig brains can be obtained from Chinese and Mexican markets, while halal butchers may carry calf, sheep, or goat brains.

But brains aren’t the only ingredient that might prove difficult for modern cooks to obtain. Apicius, for example, tells us to grind fresh rose petals, moisten them with fish sauce, and strain to extract their essence. A simpler method is to use store-bought rose water, found at Middle Eastern and South Asian grocery stores, which is collected by distilling the steam from boiled petals.

Apicius calls for regular grape wine (red or white is not specified) as well as passum, a sweet “straw wine” made by fermenting dried raisins instead of fresh grapes. Some Italian dessert wines such as passito (derived from passum) and vin santo are still made according to the same method. Substitute any dessert wine, or a sweet fortified wine such as port or sherry.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook