The Weird, Wonderful World of Collecting French Cake Figurines

Porcelain or plastic, Harry Potter or copulating couple, fèves come in all shapes and sizes.

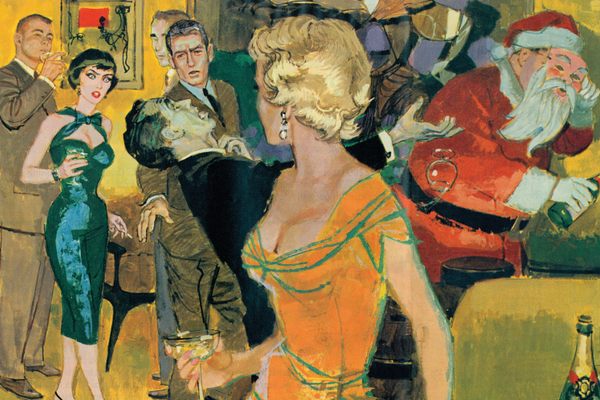

Each January, French families unite around the frangipane-stuffed puff pastry known as galette des rois, an Epiphany staple now enjoyed throughout the month. Along with glasses of cider or Champagne, the assembled dig into their slices, carefully, in hopes of being designated king for the day by the presence of an inedible trinket known as the fève.

Fève originally means fava bean, an allusion to similar winter solstice traditions dating back as far as ancient Rome, with favas signifying spring’s arrival. It wasn’t until the Middle Ages that the fava bean was replaced by a porcelain trinket, fashioned, by the 19th century, in a panoply of shapes both religious and profane. According to Cyrinne Prudhomme, religious shapes like baby Jesus or Joan of Arc gave way to good luck charms like horseshoes. By the 20th century, fèves were designed in the shapes of newsworthy items like the Concorde jet or a zeppelin, with plastic overtaking porcelain as the material of choice and cartoon characters becoming the shape du jour.

And Prudhomme should know: Since the tender age of five, she has been what, in France, is termed a fabophile. These avid collectors of fèves haunt flea markets and garage sales, unite on Facebook, and meet at exhibition shows, all to amass troves of fèves numbering the tens—or hundreds—of thousands.

Véronique Fontanel and her daughter Anaëlle began their collection a bit on a lark, in 2020.

“One of my daughters was born in January, my husband was born in January, and my nephew was born in January,” lilts Fontanel in her Southern French accent, on a call from her home in Montesquieu. “So our birthday cake has always been a coque.” The coque is the Southern answer to the galette, a ring of brioche topped with fruit or pearl sugar.

“We like coques better than galettes,” she says. “And of course, there’s always a fève inside.”

The mother-daughter pair shared their modest assortment of 20 fèves on Facebook, and soon, friends and family were donating their own to the nascent collection. Three years later, they have amassed about 3,000.

Fabophile Thierry Storme, too, says that his collection started on a whim, but for the 73-year-old retiree, it has since become an obsession, motivated in large part, he says, by his extraverted nature.

“I don’t smoke; I don’t drink. But I have a passion for meeting people,” he says. In the small village of Champagne-sur-Oise, Storme organizes events and leads local associations. After founding a Postcard Collectors’ Club, he discovered there was also a demand for a similar organization devoted to fèves.

“No one wanted to pick up the torch,” he says. “So I did.”

Fabophiles generally divide fèves into two categories, with modern fèves—those produced post-1950 and often made of plastic—being the less sought-after of the two. More beloved by collectors are première époque or first-era fèves, which date to between 1870 and 1940. These were produced in large part by Limoges Castel, a specialist in French porcelain production that, at its peak, turned out several million fèves a year, ranging from bas-reliefs to medallions and depicting everything from religious statuettes to exotic animals. Such made-in-France fèves are rare these days, according to Storme. Limoges Castel ceased production in 1988. “And of course since 1900, there were two wars, after all,” he says. “So lots of things have disappeared.”

While some modern artisans have made their own contributions, few remain. Paul Delmas was the mastermind behind Pagis Fèves, a small production facility in Normandy. His intricate fèves came with an incredible attention to detail, such as a ship whose sails billowed with imagined wind or a donkey sporting a particularly ornery expression.

“He was kind of our god,” Storme says of Delmas. “When you were lucky enough to speak with him, you could just be there in admiration of what beautiful things he made.”

Delmas passed away in 1988, leaving behind a legacy now burdened with rampant counterfeiting.

While some fèves, like those from Pagis, are sought-after for their rarity, others glean their value from their leanings toward the risqué, such as a collection depicting the kama sutra. For others, it’s a blend of both, like one collection produced in 1943 barely evoked by fabophiles, who keep its existence a near secret. The 13 fèves were a special order for a party of Nazi officers; possession of one of them granted entry into a special erotic room for swingers, and each fève was emblazoned with a swastika.

“I would prefer a plane, or a dragonfly, or something like that,” says Storme, who owns two of these fèves. “This one, it’s got a history to it that is anything but banal, but you don’t show that to people.”

Secrecy is omnipresent in the fabophile community, and not just when it comes to fèves evoking genocide. Storme has refused visits from TV crews seeking to film his collection out of fear he will be burgled.

“When you’ve spent 40 years collecting, and one day you come home and you can’t find your collection…well, that would be heartbreaking,” he says. While most fèves’ monetary value is low, with 80 to 90 percent of modern fèves, according to Storme, fetching between one and three euros, some first-era fèves can fetch 1,000 euros or more.

Storme may prefer these fèves, but other collectors, like Fontanel, lean toward contemporary ones. And these fèves are perhaps tailor-made for collectors, renewed each year and released in sets of eight to twelve.

Most are designed to appeal to children: Astérix or Harry Potter, Paw Patrol or Star Wars. A self-professed kid at heart, Fontanel’s favorites are the Disney fèves, and she’s amassed quite a number of spotted Dalmatians, not to mention a gilded cast of Winnie the Pooh. Her daughter Anaëlle loves Hello Kitty. Each year, they attempt to complete an entire set, a goal that, despite their love of coque, often means they have to become eagle-eyed bargain-hunters.

“Last Sunday, we went to 15 garage sales,” says Fontanel, noting she can often find fèves at just 10 to 20 cents. “I wouldn’t pay more than two euro, though. I mean it’s just a fève.”

Their 3,000-strong collection is minute in comparison to those of others, like a Burgundian former schoolteacher, who in 25 years has amassed 130,000. Storme, meanwhile, doesn’t know how many fèves he has; he’s never counted. His collection seems to hinge more on the community than quantity. In addition to founding his local collectors’ club, he is the organizer of the Salon Mondial de la Fève, France’s biggest exhibition show devoted to fèves, where fabophiles can meet and trade their bounty.

Fontanel and her daughter attended their first salon when Anaëlle was just 10.

“It was marvelous,” she recalls. “We really didn’t want to leave. There were so many collectors. And there was an old grandpa who said, ‘Wait, you’re collecting fèves? You’re so young!’ And he gave her tons of Harry Potter ones.”

This “grandpa” may well have been Storme, who makes a point of giving away as many as possible, especially to children.

“We’ve got thousands to give, so we give them,” he says. “They’re so happy, and they leave with a smile, and then they want to come back. And then of course, they’ll be the collectors!”

Finding a new generation of collectors is important to Storme. He started his own collection of fèves with his daughter, when she was just eight; six years ago, she died from breast cancer.

“She was supposed to inherit my collection,” he says. “My granddaughter isn’t interested, and that worries me a bit. Because what am I going to do with it? It was for her.”

He’s not the only one beginning to think about what will happen to his collection when he’s no longer around. He recalls one gentleman seeking him out after the deaths of his wife and daughter. Both were avid collectors, and the man was now faced with countless fèves.

“Their story touched me. So I bought them all.”

For now, Storme says, he’s going to maintain his own collection, though the idea of his family being saddled with it once he’s gone does trouble him.

“If I meet someone who wants it all, maybe I’ll get rid of it, but for the moment, I don’t want to,” he says. “It’s like a baby, a collection. You want to keep it all the way to the end.”

Despite Storme’s worries, however, 15-year-old Anaëlle is perhaps evidence that this tradition will go on. She loves spending time with her mom at garage sales; to hear Fontanel tell it, she’s far better at remembering which fèves they already have and which they’re missing.

Anaëlle has also just begun her first year of culinary school to become a baker, and she’s become a specialist of homemade coques. But when it comes to the fève to be slipped inside, not any old fève will do.

“We have special ones,” Fontanel cautions. They’re duplicates, she adds. “Not the ones from the collection, of course.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook