The Magic Spells That Herded Medieval Bees

For European beekeepers, “swarm charms” were once a tool of the trade.

If you had a problem in Early Medieval Europe, chances were good that there was a spell for it. “Metrical charms” were sets of magical instructions for addressing dilemmas with spoken words and actions that combined herbal medicine, prayer, and ritual. Many dealt with the challenges of agriculture, with Old English examples having titles like “For Unfruitful Land,” “For Lost Cattle,” and Wiþ Ymbe, meaning “For a Swarm of Bees.”

Although it was discovered copied into the margins of an 11th-century manuscript, “For a Swarm of Bees” is believed to be older, from the ninth century. It’s one of the earliest examples of a subset of metrical charms called “swarm charms.” These were magic spells once used by beekeepers across Europe to control and direct their precious honeybees and prevent them from flying off when they gathered into a swarm. “For a Swarm of Bees” begins with physical instructions and ends with what you should say to the bees:

“Take [some] earth, throw it with your right hand under your right foot, and say:

‘I catch it under foot, I have found it. Lo! Earth has power against all and every being, and against malice and against mindlessness, and against the mighty tongue of man.’

And then throw dust over the bees when they swarm, and say: ‘Sit you, victory-women, settle to earth! Never must you fly wild to the wood. Be you as mindful of my welfare as each man is of his food and home.’”

Tossing dirt over the bees would have been just as important as the magic words; perhaps more important, since it would have produced the desired result of getting the confused insects to settle on the ground en masse. The bees are addressed as “victory-women” (sigewif, in Old English) because this term was also used for Valkyries and warrior women, and like them, worker bees are females who wield a “sword” (their stinger). Other swarm charms gave the insects pet names like “little animals,” “beauties,” or “dear ones,” in languages from German to French to Greek. Though most examples come from the Medieval era, swarm charms persisted until as recently as the 19th century, when changes in beekeeping made them obsolete. Experts suggest that new technology and cultural shifts like the Scientific Revolution ushered in a new approach to beekeeping that was less reliant on magic and more conscious of why and when bees swarm.

Today, we understand that a colony of bees functions as a collective “superorganism,” and swarming is “a way for the superorganism to reproduce, and spread those genes around,” explains Gene Kritsky, dean of the School of Behavioral and Natural Sciences at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati, Ohio. Originally an entomologist, Kritsky is an expert on the history of beekeeping, though his research has also covered topics from dinosaurs to Darwin. “I have worked on periodical cicadas as one of my primary areas, and you’ve got to do something in between those 17 years,” he jokes.

Kritsky explains that when a beehive starts to get overcrowded, typically in early summer, the queen leaves the hive with about two-thirds of the bees clustering around her, following her trail of pheromones. While the swarm scouts for a new place to live, the remaining bees rear a new queen, who will mate and keep the original colony going by laying eggs. “One of the major activities the beekeeper does is to sit there and watch,” Kritsky says. Modern beekeepers keep an eye out for signs of swarming and provide ample growing space for their colonies, including empty hives for swarms to move into.

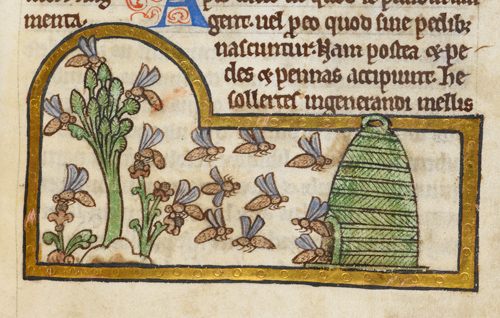

Dividing colonies by moving swarms into new hives was even more essential to beekeeping in the Middle Ages, because of the different methods Medieval beekeepers favored. Early beekeepers in northern and western Europe kept their insects in simple woven straw or wicker hives called skeps, from an Old Norse word for “basket.” Today, skeps are banned in the United States because they are difficult to inspect for disease, but they’re still available in Europe, and were once so common that they became the basis for the dome-shaped, stylized beehive seen everywhere from the state seal of Utah to Winnie the Pooh.

Today’s boxlike wooden beehives, invented in the 1850s, have removable frames in which the bees are encouraged to exclusively deposit honey while rearing their young in other frames. This allows honey to be extracted from the hive without harming the insects. With skeps, the entire nest had to be scooped out and destroyed to harvest honey and beeswax, which was typically done after killing the colony of bees with smoke.

Skeps were made small to encourage bee colonies to split off into swarms, which could then be gathered into empty skeps to start new colonies. At the end of each summer, Medieval beekeepers would kill some of their colonies for the honey harvest, allowing others to overwinter as “stock hives” to replenish the population. Because of this cycle, a beekeeper might have two or three times as many active skeps in summer as they did in winter and spring. Moving swarms into skeps required the use of swarm charms in conjunction with physical practices, like throwing dirt over the bees and “tanging,” the rhythmic banging of two metal objects such as two pots, which can also help direct the movement of the swarm. While we don’t know of any recorded swarm charms older than “For a Swarm of Bees,” the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder described the practice of tanging in the first century, writing that “to cause a swarm of bees to settle, you must strike on bronze vessels.”

Kritsky describes swarm charms as “very much of an ecclesiastical thing.” “For a Swarm of Bees” is unusual among charms of its era for not making explicit Christian references. The “Lorsch Bee Blessing,” composed in Germany around the same time, asked the bees to “please sit quietly and work God’s will.” Instead of being told “Sit you,” the German bees received a Christian scolding: “the Virgin Mary commands you to sit! You don’t have permission to fly off to the woods.” Similarly, a French swarm charm asked the colony of “beauties” to settle down with the reminder that “the beeswax is for the Blessed Virgin, and the honey is mine.”

Many such charms would have been composed and used by Medieval monks and nuns, who widely practiced beekeeping for a number of reasons. Beeswax was considered a pure, noble substance and the most-suitable medium for church candles, in part because bees were thought to be chaste, asexual creatures, perhaps born spontaneously from flowers. Bees were also seen as symbolic of an orderly Church hierarchy, with one Medieval bishop comparing a hive to a hardworking convent, though he held the misconception, common at the time, that the queen was a male “Magistrate” who oversaw the worker “nuns.”

There was also a desire on the part of Medieval church officials to control the lucrative trade of honey—a luxury that provided the only source of concentrated sugar in the Medieval European diet—and to limit the consumption of alcoholic mead, traditionally fermented from the leftover dregs of the honey harvest in pre-Christian northern Europe. Many swarm charms asked bees to be good and produce their honey “for the Church.” Kritsky points out that some Medieval beekeepers would have been permitted to pay the tithe owed to the local Church in skep hives.

In the 1960s, folklorist Austin Fife’s analysis of known swarm charms found that 96 percent of charms from before the 17th century included Christian references, compared to 58 percent of examples from the 18th to 20th centuries. “As beekeeping becomes more rational,” says Kritsky, “they’re removing some of the overt Catholic or Protestant phrases.” “Rational beekeeping” refers to a more scientific, less-mystical approach that includes an increased understanding of the biology of bees. Kritsky points out that in sources from after the Medieval era, “a lot of times they talked about tanging, but they don’t mention the phrases” that go along with it, in contrast to earlier sources that wrote down the charms but didn’t always describe the tanging. This suggests a growing understanding that it was the tanging, not the words, that influenced the swarm.

Our modern wooden beehives were invented in the mid-19th century, which is around the time Kritsky suggests that people stopped using swarm charms. He describes “a growing movement starting in the 1700s, and more so in the 1800s, to no longer kill your bees.” Even before the development of hives with removable frames, this was accomplished with new methods that Kritsky says might be considered “the next innovation of tanging.”

“Driving the bees” involved transferring the skep to a pail and rhythmically banging the outside, forcing the colony out of the skep, after which they could be moved into a new one. Another bee-saving technique of the 19th century was to place a glass jar, open at the bottom, on top of the skep. Because this jar was held at a lower temperature than the warm interior of the hive, the queen would not enter and lay eggs there, meaning the bees would use it only for storing honey and not for rearing babies. When the jar had filled up with pure honeycomb, it could be removed and even brought directly to the breakfast table for serving.

“Beekeepers have been pretty ingenious over the years, developing new technologies,” says Kritsky. As beekeepers have innovated new methods, they have also discarded older ones. When Western settlers introduced the European honeybee to the Americas in the colonial era, they left swarm charms behind, and even tanging has not seen much use in modern American beekeeping. Wooden hives, Kritsky explains, “were expensive in Europe, but there was so much wood here they could have wooden beehives. And so we don’t see a lot of skep beekeeping going on in the U.S.”

With the increase of wooden hives with removable frames and “rational beekeeping,” there was less of a need to verbally beg swarms to stay in one place. Are magic words even necessary, since it was really the tanging and other physical actions that did the trick? At some point “they realized,” Kritsky muses, that “the bees aren’t listening.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook